I hate it when my horse is in pain or isn’t feeling well! She is genuinely one of my best friends; I’d be lost without her. To keep her from suffering, I always try my best to make sure she’s in perfect health. Regular exercise is a must; trotting, cantering, lead changes, and jumping all keep her body as well as her mind engaged. Since I want my mare to be healthy and strong for years to come, I did some research on the equine digestive system after talking to our vet. Because horses are grazing animals, they need to eat consistently throughout the day. This blog will explain what I’ve learned so you can also understand the fascinating and vital basics of a horse’s digestive system. After all, you must comprehend how their digestive tract works to ensure you’re caring for your horse as best as you possibly can.

Where Does It All Begin?

Your horse’s digestive system starts in his or her mouth. Did you know that a horse’s chewing movement is both lateral and vertical? Because of this, your equine BFF needs strong, healthy teeth. Horse owners should realize that our equine friends are designed to eat grass or hay, not grain. So it’s imperative to feed your horse top-quality horse forage—oftentimes pleasure horses don’t require any grain in their diets at all. Forage in the form of hay and pasture grass is plenty. Too much grain, which is high in sugars and starches, may bring on colic.

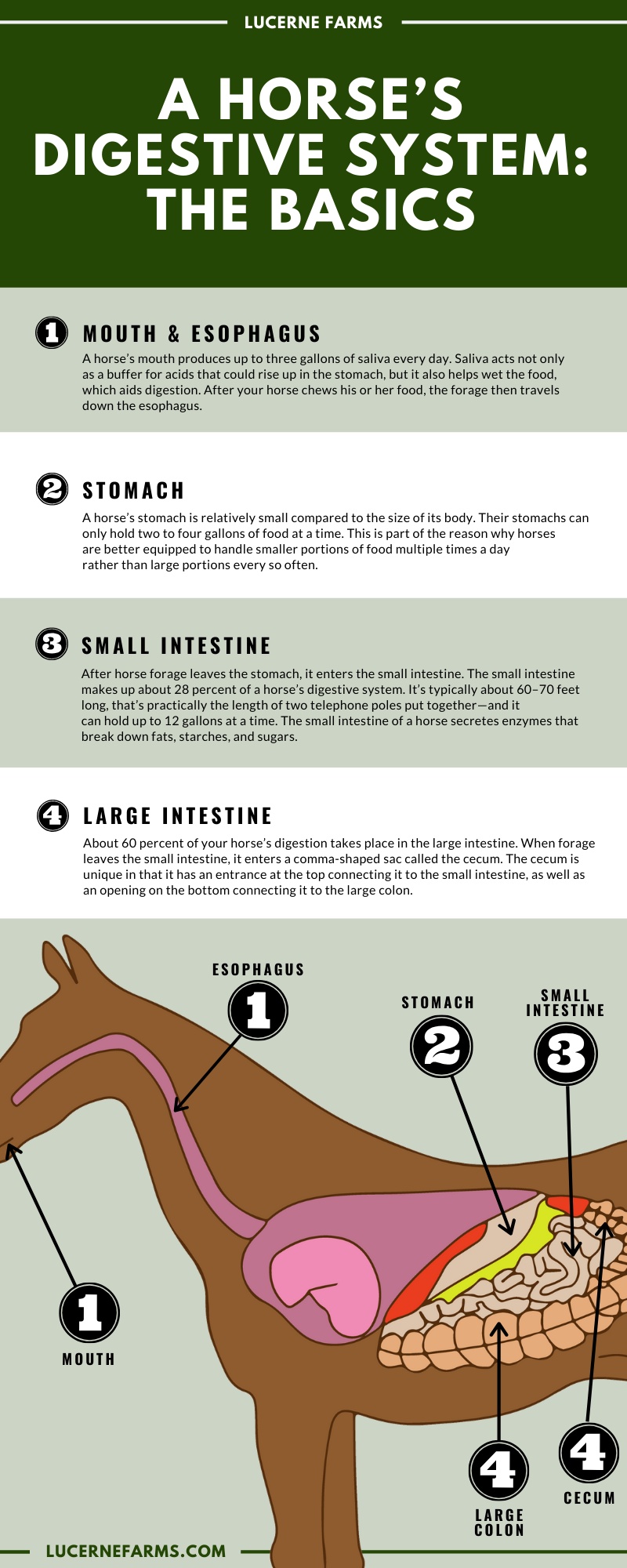

Here’s another fun fact: a horse’s mouth produces up to three gallons of saliva every day. Saliva acts not only as a buffer for acids that could rise up in the stomach, but it also helps wet the food, which aids digestion. After your horse chews his or her food, the forage then travels down the esophagus. Unlike humans, a horse’s esophagus is a one-way tunnel. Every horse owner learns early on that a horse cannot vomit. Because their esophagus is a one-way funnel, this prohibits them from vomiting like other animals or humans can. The problem with this, of course, is that their inability to vomit means digestive disturbances can quickly lead to life-threatening colic.

The Stomach and Small Intestine

One of the most surprising things I came across when doing my research on horse digestion is that a horse’s stomach is relatively small compared to the size of its body. Their stomachs can only hold two to four gallons of food at a time. This is part of the reason why horses are better equipped to handle smaller portions of food multiple times a day rather than large portions every so often.

The lower half of your horse’s stomach is lined with a layer of mucus that protects it from acidic fluids or substances. The upper portion of your horse’s stomach is more susceptible to acidic irritation. Because of this, horses are prone to ulcers. The best way to prevent your horse from developing an ulcer is to keep their stomach full. Horses are more likely to get ulcers when their stomachs are empty, causing acid to rise up. Follow nature as closely as possible and make sure your horse feeds consistently throughout the day, which mimics the grazing process.

After horse forage leaves the stomach, it enters the small intestine. The small intestine makes up about 28 percent of a horse’s digestive system. It’s typically about 60–70 feet long, that’s practically the length of two telephone poles put together—and it can hold up to 12 gallons at a time. The small intestine of a horse secretes enzymes that break down fats, starches, and sugars. Pancreatic enzymes help to digest the food further while carbohydrates digest sugars and starches.

Most of the carbohydrate and amino acid digestion takes place in a horse’s small intestine. A substantial number of vitamins are absorbed in a horse’s small intestine, too. It takes about 30–90 minutes for the food to pass through a horse’s small intestine. Once digestion in the small intestine is complete, the food is absorbed and carried through the bloodstream.

Since the small intestine plays such a crucial role in a horse’s digestion, we as owners must ensure that it’s functioning properly! If the minerals aren’t absorbed, our equines won’t receive the nutrients they need.

Where the Magic Happens

I can’t emphasize the importance of a horse’s large intestine enough. About 60 percent of your horse’s digestion takes place in the large intestine. When forage leaves the small intestine, it enters a comma-shaped sac called the cecum. The cecum is unique in that it has an entrance at the top connecting it to the small intestine, as well as an opening on the bottom connecting it to the large colon. The cecum is the optimal site for fermentation because it contains a ton of active microbes. The cecum can also absorb any nutrients that are created throughout fermentation. This fermentation process eventually creates vitamins that are essential to providing energy to your horse or mare.

Although microfiber fermentation does occur in other parts of a horse’s digestive system, most of it happens in the cecum. At the same time, fermentation continues in the large colon, where vitamin B is created. Ventral colons, located within the large colon, are constructed like pouches. These are designed to help horses digest large amounts of food.

Once the digestion process is complete in the large intestine, the remaining matter moves to the small colon. This is where any excess water returns to the body and forms fecal balls with the leftover material. These fecal balls are then passed on to the rectum and are finally expelled through the anus. Manure is something equestrians are rather familiar with!

To protect our best friends, we must help them follow natural feeding practices when we’re caring for them. We can’t force a human diet upon our horses—they cannot eat just one or two meals a day. Because they developed as grazers, they must eat continuously throughout the day. If they don’t, they could be prone to ulcers or conditions like colic. Properly caring for your horse’s digestive system is one of the most important things you can do for their health!